The essential truth of soccer is that whichever team imposes its will upon the other usually wins the game. We see it every week in MLS: If Real Salt Lake set up shop in the gap between the central defense and midfield, they usually win. If the Red Bulls spread you out and force you to open the game, they score. If LA are able to con you into giving space to their stars, they take all three points.

Thus, it’s a real problem that the US national team, as currently constructed, are essentially a team without a style. There are certain things the Yanks do well — set-pieces and counterattacks come to mind — but those are just trees rather than the entire forest.

That means Bob Bradley’s task over the next month is twofold: first win the regional championship and, along the way, give this US team an onfield identity.

There are some new faces in the mix for the US that should be able to help on both counts. And it starts in the back.

New York’s Tim Ream has caused no small amount of excitement in his 16 months as a professional, something that’s actually a bit of a feat for a defender. It’s the forwards and midfielders who get the glory and notice, while defenders are usually only in the spotlight for mistakes they’ve made.

But Ream’s calm, almost casual ability to play the ball from the back has captured the imagination of coaches and pundits alike. His club coach, Hans Backe, compared him to Rio Ferdinand. US soccer hall of famer Alexi Lalas recently put Ream in his All-Time US Best XI, even though he’s played just three times in US colors.

And fans went slightly agog for Ream’s display this spring against Paraguay, looking past some of his faults and instead focusing on the way he was able to turn what would usually be lost possessions into pinpoint distribution.

Ream, you see, has style. While the rest of the US team are generally better off when they’re moving 9,000 miles per hour, Ream has the ability to suck the opposition out of shape by being patient and, with one pass, open the field.

“Open field,” by the way, are the two favorite words of Landon Donovan, Clint Dempsey and the rest of the US goal-scorers.

This American team has the capacity to be devastating in transition. But as word has gotten out, chances to show as much have diminished. Paraguay hardly ventured past the midfield stripe this spring. And in last summer’s loss to Ghana, the Black Stars played an almost comically deep defensive line in extra time after being burned repeatedly by the US counter in the second half.

Teams now know to make the Yanks play patient. That’s the best way to marginalize and isolate Donovan and Dempsey, and it puts pressure on the defense and central midfield to create, rather than destroy, the pace of the game. Ream excels there; the other US defenders do not.

Tactics, though, have as much to do with this as personnel. Since the World Cup, Bradley’s been married to a “Double 6” formation with two deep-lying midfielders. It’s a system that’s largely run its course on the international level, and it’s done the US no great favors on either side of the ball.

In the Double 6, slight lapses in communication can lead to exposure in the “red zone" — that area 25 to 40 yards from goal where most of the goals the US concede are born — and it forces the central midfield pair to play more laterally. That is double-plus ungood for a counterattacking team which, by definition, wants to get vertical.

It also can complicate the game for the defenders, a major worry when your central defense is short on either experience (Ream) or skill (everyone else).

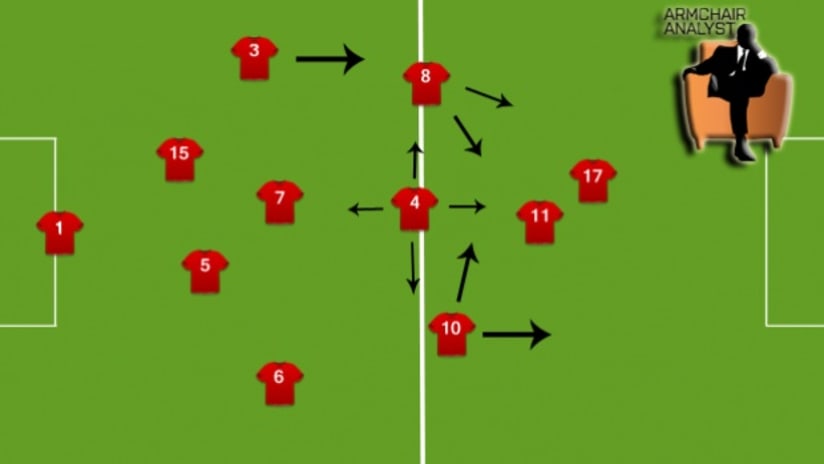

The solution, which is frustratingly obvious for long-time observers of the team, is to play with a pivot, or a fulcrum, or a back point, or a true d-mid. Whichever term you want to hang on it, the job is the same: Protect the backline and let the other central midfielder play higher up the pitch.

That allows the game to become vertical. The opponent gets stretched, and with that comes passing lanes. With passing lanes comes the chance to string passes together — and the birth of a style.

It’s not a deviation from what works for the talent assembled. Michael Bradley played his best ball for both club and country in front of a pivot, and has 16 secondary assists in his 52 caps. He knows how to get the ball to the playmakers.

Maurice Edu and Jermaine Jones have both played the pivot at high levels — Edu in the World Cup and Jones in both the Bundesliga and English Premiership. They know how to protect a back line.

And the formation would put Ream’s unique talents to best use. Pushing another central midfielder higher up the pitch would give Ream more options in his distribution, and by proxy partially lifts the creative burden from Donovan and Dempsey. Getting them into space with the ball at their feet should be the goal, and it’s something Ream will be able to do if he’s not shackled by the uncertainty of the Double 6.

Is it enough to add up to a style for the US? A go-to gameplan that the Yanks can impose upon weak or unwary opponenets? Evidence from the World Cup — the US played with Edu as the pivot against Slovenia in the second half, all of the Algeria game and against Ghana after the half-hour mark — says yes.

For better or worse, there’ll be more evidence by the end of the month.

Matthew Doyle can be reached for comment at matdoyle76@gmail.com and followed on Twitter at @MLS_Analyst